Equity in poker is the share of the pot that is yours based on the odds that you will win the pot at that point in play. Equity changes after each street – pre-flop, flop, turn and river. Equity denial is when you prevent a player from realizing his equity by forcing him to fold before showdown. So, if you fold a hand that had 40% equity to win the pot versus a flop bet, you were denied 40% equity. This concept becomes less and less applicable the deeper you are in the game-tree (visualized below). PREFLOP FLOP TURN RIVER. Practice defining ranges away from the table. Every player's range is shaped by their previous. If you have more than 50% equity in the hand, you want to get as much money in the pot as possible. It may be the case that the river brings another J or T giving our opponent the better hand with a full house, but this fact is irrelevant on the turn when we have 91% equity.

- Poker Range Equity

- Poker Equity On Turn And River Cruises

- Poker Equity On Turn And River

- Poker Equity On Turn And River Flow

Understanding how equity works in poker can be a difficult task for even seasoned players. When you start talking about hand equity versus ranges and how to use that information to play better poker, confusion can creep in and it's difficult to sort out why the heck any of this math stuff really matters. The real problem is that while learning the definition of equity is easy, the hard part is figuring out how to implement that information into your poker game in a practical way.

Today, while most players now understand what equity is, being able to translate that information into quality decisions remains a mystery. The goal of this article is to broaden your understanding of how post-flop equity works and help clarify how to form better post-flop lines against your opponents.

What is Equity in Poker?

One of the keys to winning at poker is learning how to play a variety of different types of hands after the flop. The first step is recognizing whether your hand has enough value to warrant contributing more chips to the pot. This is where the rubber meets the road and an understanding of math becomes important since the way we measure the value of a hand is through equity.

Equity is defined as the share of the pot that each player involved in a hand owns based on the mathematical likelihood of their current holding winning by the river. As streets progress from pre-flop to flop, flop to turn, and turn to the river, equity changes until the final equity is achieved on the river. Equity can change a maximum of three times during a Texas Hold'em hand.

Equity = Percentage Chance of Winning By The River

Example Equity Calculation Between Top Pair and a Flush Draw

Using Equity to Make Decisions

While we do not know the exact hand that our opponents hold, we can make reasonable assumptions about our equity versus their range. This information contributes to our making quality decisions at the poker table. However, just knowing the equity of your hand versus a range doesn't really help you optimize your lines since there are different types of hands in our range that lead to similar equities. In other words, sometimes holding a draw or a pair will give us a similar equity to our opponent's range.

In order to clarify the decision-making process, I find it helpful to further subdivide equity down based on how different holdings play out versus the ranges of our opponents. The logical way to do this is to separate the equities of our range into two categories: made hands and drawing hands. The reason it is useful to divide our range this way is because, versus opponent ranges, made hands play very different than draws as streets progress. In fact, how those equities change as a hand plays out is the main theoretical difference between made hands and draws.

What is a Made Hand?

A 'made hand' is associated with having a pair or better and does not need to improve further to have a chance of being the best hand by the showdown. There are generally very few cards that can further improve a made hand. For example, if you have one pair, there are potentially only 5 cards left in the deck that would either give you two pair or three of a kind.

Made hands come in varying strengths and can be categorized three different ways:

- Monster Hands

Monster hands are hands that are better than one pair. Examples include two-pair, trips, straights, flushes, and full houses. - Strong Hands

This includes overpairs and most top pair hands. - Marginal Hands

Marginal made hands include middle pair, bottom pair, and under pairs to the board. Any hand less than top pair is usually marginal since they are vulnerable to any number of other made hands.

What is a Drawing Hand?

A drawing hand or 'draw' is when you have a hand that is not likely the current best hand but has several 'outs' to improve to the best hand by the turn or river. The most common draws that come to mind for people are flush draws and straight draws. Here are a few examples of draws along with how many potential outs each might have.

- Two Overcards: 6 Outs

- Open-Ended Straight Draw: 8 Outs

- Two-Card Flush Draw: 9 Outs

- Two Overcards and a Gutshot Straight Draw: 10 Outs

- Flush Draw and One Overcard: 12 Outs

- Open-Ended Straight Draw and Two-Card Flush Draw: 15 Outs

Understanding how basic equity and pot odds work with draws are basic fundamentals of poker. In this article, we will focus on taking another angle and explore an advanced way of using equity to help us make better players after the flop.

The Equity of Made Hands Versus Draws

Both strong made hands and strong draws tend to have a lot of equity on the flop. The difference between the equity of a made hand versus a draw is that the former tends to have fairly constant equity versus an opponent's range on the flop, turn, and river but does not fair well if our opponent improves. In other words, if you have a made hand like top pair and are ahead of your opponent's range, then it is very likely that you will have a similar equity on the turn and the river. The equity will not go down or up much and will remain relatively stable. But, if your opponent does improve, you will likely be far behind their equity. A draw works very differently as your equity will vary wildly from street to street. However, a draw will maintain it's equity fairly well no matter how strong an opponent's range is. This is called the concept of stable and variable equity.

Stable Versus Variable Equity

Before we can discuss how to use the differences between the equity of made hands versus draws, first we must change how we think of them. This requires that we revise their definitions. By categorizing our holdings based on the dynamics of equity, we can redefine made hands and draws as follows:

- Made Hand

A hand with stable equity with the progression of streets and variable equity across ranges. - Draw

A hand with variable equity with the progression of streets and stable equity across ranges.

What this basically means is that a made hand tends to maintain its equity over multiple streets but has a much weaker equity as our opponent's range gets stronger. Conversely, a draw will tend to lose equity as streets progress but has strong equity against a wider range of hands.

Understanding Equity

Try to picture in your head how your equity looks with a made hand versus a medium to weak range. On the flop, you are way ahead, and on the turn, you are almost always even further ahead. Therefore your equity is 'stable' over progressing streets. On the other hand, imagine that you have a draw against a weak made hand and miss your draw on the turn. Your equity will now be a lot less than it was on the flop, meaning your equity is 'variable' over progressing streets.

Now think about how a made hand looks against a range of hands that includes a few really strong hands in it. Since you are way ahead against a lot of hands and also way behind against some of the hands, you have variable equity across the various hands, or ranges, your opponent could have. Conversely, if you have a draw, your equity is pretty much the same against nearly the entirety of your opponents' made hands. In other words, you have stable equity across the range of hands.

To illustrate, let's do some Pokerstove calculations to see how this works. First, we'll take a look at the equity of made hands.

The Equity of Made Hands

A made hand is said to have stable equity as streets progress. In the first example, let's give our opponent a range that might continue on a particular flop.

Hero's Hand: AK

Flop: K♠ 7♦ 2♣

Hero Range: 73.737% { AK }

Villain Range: 26.263% {22, 77+, AK, KT+ }

——————————————————————————–

Turn: K♠ 7♦ 2♣ 9♥

Hero Range: 72.252% { AK }

Villain Range: 27.748% {22, 77+, AK, KT+ }

——————————————————————————–

River: K♠ 7♦ 2♣ 9♥ 4♠

Hero Range: 76.119% { AK }

Villain Range: 23.881% {22, 77+, AK, KT+ }

Notice how the hero's equity remains stable street by street, starting at 74% on the flop, changing to 72% on the turn, and finishing at 76% on the river. Now let's look at how the equity of a made hand changes as a range narrows only leaving the strongest hands in our opponent's range.

Flop: K♠ 7♦ 2♣

Hero Range: 74.293% { AK}

Villain Range: 25.707% {22, 77+, AK, KT+ }

——————————————————————————–

Flop: K♠ 7♦ 2♣

Hero Range: 45.833% { AK }

Villain Range: 55.644% { KK+, 22, 77, AK, KQ }

When the range narrows to a much tighter range, the hero's equity drops a full 30%. This is how made hands have variable equity over different ranges. Now let's look at similar examples where we have a draw in place of a made hand.

The Equity of Draws

A draw is said to have variable equity as streets progress. Let's look at another example to illustrate this concept.

Hero's Hand: A♠Q♠

Flop: K♠ 7♠ 2♣

Hero Range: 44.348% { A♠Q♠ }

Villain Range: 55.652% {22, 77+, AK, KT+ }

——————————————————————————–

Turn: K♠ 7♠ 2♣ 9♥

Hero Range: 25.612% { A♠Q♠ }

Villain Range: 74.388% {22, 77+, AK, KT+ }

We have lost almost 20% in equity in one street. If our hand doesn't hit on the river, our equity will be 0%. Therefore, our draw in this example has variable equity from street to street.

Now, let's narrow our opponent's range again and see how that affects the equity of a draw.

Turn: K♠ 7♠ 2♣

Hero Range: 44.348% { A♠Q♠ }

Villain Range: 55.652% {22, 77+, AK, KT+ }

——————————————————————————–

Flop: K♠ 7♠ 2♣

Hero Range: 36.478% { A♠Q♠ }

Villain Range: 63.522% { KK+, 22, 77, AK, KQ }

We took away all but the nut hands and we still only lost 8% equity. This shows how draws have stable equity over ranges.

You may be thinking, 'this is great, but how do I use this information?.' The answer lies in the particular lines or actions you take with various holdings.

Using The Concept of Stable & Variable Equity

Here are a few inferences that we can take away from what we have learned so far:

- Stable equity over multiple streets hands (made hands) play better against weaker ranges and benefit from multiple rounds of betting.

- Hands with variable equity over multiple streets (draws) play better against stronger ranges and benefit more from aggressive play on early streets.

- The fewer hand combinations we beat, the better it is to have stable equity over ranges (draws).

- The more hand combinations we beat, the better it is to have variable equity over ranges (made hands).

- Against straightforward opponents, you will tend to have more equity when you semi-bluff shove and get called than if you shove with a made hand.

- Made hands benefit from getting to later streets; draws benefit from ending the hand early.

Now we use these assumptions to our advantage and figure out the best way to play each hand based on the type of equity it has. As you read further, keep in mind that the suggestions I make are very general and based on looking at the player pool as a whole. Against strong or tricky opponents who are good at hand-reading, you must adapt your lines accordingly when trying to form profitable lines and optimize your c-bet frequencies.

How To Play Made Hands

Since we know that made hands have stable equity as streets progress, we generally want to play straightforward and build pots when our opponent's range is weak. The standard play should be to go for as many streets of value as possible. With mid-strength made hands, bet-folding is our friend against most opponents. By bet-folding, I mean you bet for value and then fold if raised. This works best against most weak opponents and ABC type opponents.

However, when our opponent's range for continuing is narrow, we want to avoid building giant pots unless SPR dictates otherwise. When an opponent's range is strong, we tend to want to pot control more often and try to get to showdown without building huge pots. Taking more passive lines such as checking back the flop is often warranted when it's hard to get value from worse hands. Instead, we benefit from keeping in the weaker parts of an opponents range which we can bluff catch against on later streets.

How To Play Draws

With variable equity as streets progress, we know our equity will take a nosedive if we don't get there on the next street. There is no benefit to stringing our opponents out over multiple streets. Therefore, when we have high equity draws, we generally want to exert maximum pressure against the weak to medium strength hands in our opponent's range. The idea is to elicit folds with a profitable frequency based on fold equity.

The standard play should be to try to leverage your stack on the flop or turn whether against strong or weak ranges. A typical line is to go for flop check-raises or turn check-shoves out of position against aggressive opponents. In position, making slightly larger bets, in general, is also a good tactic when playing a draw. Whatever line you think will exert maximum pressure against the weaker made hands in your opponent's range is key. Just represent whatever your opponent will believe to be legitimately strong, whatever that happens to look like in a particular dynamic based on his perceived level of thinking.

The exception is when you hold a lower equity draw. In that case, it is often better to take whatever line will allow you to realize equity with a higher frequency. The balance between collecting on fold equity and equity realization is a constant struggle for good players and something you will need to actively work on.

Equity Denial

Equity denial is a concept I have been talking about for several years that has finally come to the forefront of poker thinking. Basically, it means when your opponent is forced to fold a reasonable amount of equity against your hand or range. In my opinion, the concept is basically the same as protection and mostly applies to when you have a weak made hand and are looking to 'protect' the hand versus the parts of your opponent's range that are too weak to continue to aggression but have a fair amount of equity against you. In other words, equity denial is an argument against pot controlling marginal made hands, especially on a dynamic board where there's more potential for an opposing range to catch up.

However, this does not mean that we should just go hog wild with all of our made hands and just bet bet bet our opponents into oblivion. In fact, a large portion of made hands in our range might benefit from more passive play. For example, let's say we hold a weak top pair or a mid pair type hand and the board is QT7. This is a fairly dynamic board and our opponent will certainly have parts of his range that can give him the best hand on the next street. Even so, he also likely has numerous hands that might give him a second best hand against us as well. This fact alone often cancels out the benefit of equity denial by itself.

Additionally, if we factor in the times that aggressive opponents might bluff on the turn and/or river, pot controlling actually becomes a lot more attractive with some mid-strength and even weaker strength made hands. The better we get at reading hands and opponents, the better we can pick and choose particular runouts to bluff catch or even raise our opponent off better hands on later streets.

Which Hands Should We Protect or Deny Equity?

In my opinion, the only hands we should really ever be protecting just for the sake of denial are weak made hands that will very often be caught up with by the river anyway. Underpairs and bottom pairs are the best candidates. Every other part of our made hand range benefits from more nuanced play with specific adjustments against each opponent we face. Basically, what I am saying here is that we should be careful in using 'equity denial' as a reasoning for betting except in very specific instances. Most of the time there are other factors that we should be considering, namely our equity type versus our specific opponent's range, in making betting line decisions.

Equity in Multi-Way Pots

When we look at how variable and stable equity works, we can make a couple of assumptions about how being multi-way might affect the value of a made hand versus a draw. First off, we know that against stronger ranges it's better to have a draw. Secondly, we know that made hands like top pair go down in value the more ranges that are involved in the hand. It only makes sense that the more ranges you add to the mix, the stronger your hand will need to be in order to profitably stack off.

Therefore, when holding a mid-strength made hand, we should be more inclined to play a pot control type line when involved in a multi-way pot. Conversely, we should theoretically play draws (to the nuts) much more aggressively the more ranges we are up against. This is partially due to the increased amount of dead money in the pot but also because something magical happens when we end up in a multi-way situation against two strong ranges on the flop. Take a look at the following Pokerstove examples:

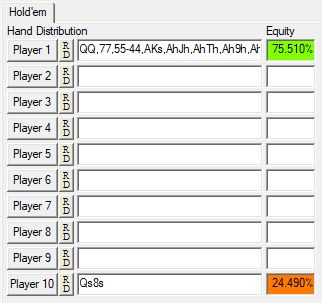

Draw Versus Two Made Hand Range

In the first example, we have an Ace-High flush draw versus a range of made hands on a K72 board. We have a respectable equity of 40%. In spots where we have only a small amount of fold equity, we can profitably stack off most of the time. In the second example, look what happens when our flush draw is up against two made hand ranges. We are actually quite a bit ahead of both of them! In this spot, we would gladly get the money in multi-way every single time. Even though we would only be winning 36% of the time, we would be raking in the long-term EV dollars. And, if you factor in that sometimes our opponent(s) might get the money in with an inferior flush draw, this situation becomes a fist pump. Which leads us to a conclusion.

Nut draws play extremely well in multi-way pots and often do not require fold equity to profitably commit to the pot.

Interestingly, even if you only included the absolute top of our opponents' ranges, we still would have a reasonably high amount of equity for a multi-way spot, as shown below.

This example proves the concept of stable equity over ranges, exhibited by draws.

Balancing Our Play

One of the main concerns of many stronger players is in balancing out their ranges. It's true that you have to be careful not to play one type of holding the same way every time and never take similar lines across the spectrum of your entire range. Therein lies the beauty of focusing on equity when making your post-flop decisions.

When you base your decisions on the perceived range of an opponent, you are already baking into the equation what he or she is thinking about your range. The use of stable and variable equity allows us to counter what our opponents are doing before they even have the chance to adjust to us. Only the very strongest opponents you will face will be balanced enough for us to be overly concerned about how balanced our own play is. The vast majority of your mental resources should be dedicated to an exploitative style of poker, not trying to play game theory optimal.

My advice is to build a core strategy that is inherently balanced and then make targeted adjustments based on the opponents you face. Those adjustments include equity considerations, tweaked based on stable and variable equities. It's not as complicated as it sounds, once you understand how it works in a practical way. Hopefully, this article has shed some light on the subject for you.

Summary

Overall, understanding equity in poker all comes down to the relationship between how made hands or draws play out versus opponent ranges. Among the concepts you must master to win at poker is to develop our sense of how to approach post-flop play using equity and ranges as a tool to optimize your lines based on the information at hand. By adjusting your lines according to the makeup of those ranges, you can maximize your profit while also simplifying the decision-making process.

In our poker math and probability lesson it was stated that when it comes to poker; 'the math is essential'. Although you don't need to be a math genius to play poker, a solid understanding of probability will serve you well and knowing the odds is what it's all about in poker. It has also been said that in poker, there are good bets and bad bets. The game just determines who can tell the difference. That statement relates to the importance of knowing and understanding the math of the game.

In this lesson, we're going to focus on drawing odds in poker and how to calculate your chances of hitting a winning hand. We'll start with some basic math before showing you how to correctly calculate your odds. Don't worry about any complex math – we will show you how to crunch the numbers, but we'll also provide some simple and easy shortcuts that you can commit to memory.

Basic Math – Odds and Percentages

Odds can be expressed both 'for' and 'against'. Let's use a poker example to illustrate. The odds against hitting a flush when you hold four suited cards with one card to come is expressed as approximately 4-to-1. This is a ratio, not a fraction. It doesn't mean 'a quarter'. To figure the odds for this event simply add 4 and 1 together, which makes 5. So in this example you would expect to hit your flush 1 out of every 5 times. In percentage terms this would be expressed as 20% (100 / 5).

Here are some examples:

- 2-to-1 against = 1 out of every 3 times = 33.3%

- 3-to-1 against = 1 out of every 4 times = 25%

- 4-to-1 against = 1 out of every 5 times= 20%

- 5-to-1 against = 1 out of every 6 times = 16.6%

Converting odds into a percentage:

- 3-to-1 odds: 3 + 1 = 4. Then 100 / 4 = 25%

- 4-to-1 odds: 4 + 1 = 5. Then 100 / 5 = 20%

Converting a percentage into odds:

- 25%: 100 / 25 = 4. Then 4 – 1 = 3, giving 3-to-1 odds.

- 20%: 100 / 20 = 5. Then 5 – 1 = 4, giving 4-to-1 odds.

Another method of converting percentage into odds is to divide the percentage chance when you don't hit by the percentage when you do hit. For example, with a 20% chance of hitting (such as in a flush draw) we would do the following; 80% / 20% = 4, thus 4-to-1. Here are some other examples:

- 25% chance = 75 / 25 = 3 (thus, 3-to-1 odds).

- 30% chance = 70 / 30 = 2.33 (thus, 2.33-to-1 odds).

Some people are more comfortable working with percentages rather than odds, and vice versa. What's most important is that you fully understand how odds work, because now we're going to apply this knowledge of odds to the game of poker.

The right kind of practice between sessions can make a HUGE difference at the tables. That's why this workbook has a 5-star rating on Amazon and keeps getting reviews like this one: 'I don't consider myself great at math in general, but this work is helping things sink in and I already see things more clearly while playing.'

Instant Download · Answer Key Included · Lifetime Updates

Counting Your Outs

Stable Versus Variable Equity

Before we can discuss how to use the differences between the equity of made hands versus draws, first we must change how we think of them. This requires that we revise their definitions. By categorizing our holdings based on the dynamics of equity, we can redefine made hands and draws as follows:

- Made Hand

A hand with stable equity with the progression of streets and variable equity across ranges. - Draw

A hand with variable equity with the progression of streets and stable equity across ranges.

What this basically means is that a made hand tends to maintain its equity over multiple streets but has a much weaker equity as our opponent's range gets stronger. Conversely, a draw will tend to lose equity as streets progress but has strong equity against a wider range of hands.

Understanding Equity

Try to picture in your head how your equity looks with a made hand versus a medium to weak range. On the flop, you are way ahead, and on the turn, you are almost always even further ahead. Therefore your equity is 'stable' over progressing streets. On the other hand, imagine that you have a draw against a weak made hand and miss your draw on the turn. Your equity will now be a lot less than it was on the flop, meaning your equity is 'variable' over progressing streets.

Now think about how a made hand looks against a range of hands that includes a few really strong hands in it. Since you are way ahead against a lot of hands and also way behind against some of the hands, you have variable equity across the various hands, or ranges, your opponent could have. Conversely, if you have a draw, your equity is pretty much the same against nearly the entirety of your opponents' made hands. In other words, you have stable equity across the range of hands.

To illustrate, let's do some Pokerstove calculations to see how this works. First, we'll take a look at the equity of made hands.

The Equity of Made Hands

A made hand is said to have stable equity as streets progress. In the first example, let's give our opponent a range that might continue on a particular flop.

Hero's Hand: AK

Flop: K♠ 7♦ 2♣

Hero Range: 73.737% { AK }

Villain Range: 26.263% {22, 77+, AK, KT+ }

——————————————————————————–

Turn: K♠ 7♦ 2♣ 9♥

Hero Range: 72.252% { AK }

Villain Range: 27.748% {22, 77+, AK, KT+ }

——————————————————————————–

River: K♠ 7♦ 2♣ 9♥ 4♠

Hero Range: 76.119% { AK }

Villain Range: 23.881% {22, 77+, AK, KT+ }

Notice how the hero's equity remains stable street by street, starting at 74% on the flop, changing to 72% on the turn, and finishing at 76% on the river. Now let's look at how the equity of a made hand changes as a range narrows only leaving the strongest hands in our opponent's range.

Flop: K♠ 7♦ 2♣

Hero Range: 74.293% { AK}

Villain Range: 25.707% {22, 77+, AK, KT+ }

——————————————————————————–

Flop: K♠ 7♦ 2♣

Hero Range: 45.833% { AK }

Villain Range: 55.644% { KK+, 22, 77, AK, KQ }

When the range narrows to a much tighter range, the hero's equity drops a full 30%. This is how made hands have variable equity over different ranges. Now let's look at similar examples where we have a draw in place of a made hand.

The Equity of Draws

A draw is said to have variable equity as streets progress. Let's look at another example to illustrate this concept.

Hero's Hand: A♠Q♠

Flop: K♠ 7♠ 2♣

Hero Range: 44.348% { A♠Q♠ }

Villain Range: 55.652% {22, 77+, AK, KT+ }

——————————————————————————–

Turn: K♠ 7♠ 2♣ 9♥

Hero Range: 25.612% { A♠Q♠ }

Villain Range: 74.388% {22, 77+, AK, KT+ }

We have lost almost 20% in equity in one street. If our hand doesn't hit on the river, our equity will be 0%. Therefore, our draw in this example has variable equity from street to street.

Now, let's narrow our opponent's range again and see how that affects the equity of a draw.

Turn: K♠ 7♠ 2♣

Hero Range: 44.348% { A♠Q♠ }

Villain Range: 55.652% {22, 77+, AK, KT+ }

——————————————————————————–

Flop: K♠ 7♠ 2♣

Hero Range: 36.478% { A♠Q♠ }

Villain Range: 63.522% { KK+, 22, 77, AK, KQ }

We took away all but the nut hands and we still only lost 8% equity. This shows how draws have stable equity over ranges.

You may be thinking, 'this is great, but how do I use this information?.' The answer lies in the particular lines or actions you take with various holdings.

Using The Concept of Stable & Variable Equity

Here are a few inferences that we can take away from what we have learned so far:

- Stable equity over multiple streets hands (made hands) play better against weaker ranges and benefit from multiple rounds of betting.

- Hands with variable equity over multiple streets (draws) play better against stronger ranges and benefit more from aggressive play on early streets.

- The fewer hand combinations we beat, the better it is to have stable equity over ranges (draws).

- The more hand combinations we beat, the better it is to have variable equity over ranges (made hands).

- Against straightforward opponents, you will tend to have more equity when you semi-bluff shove and get called than if you shove with a made hand.

- Made hands benefit from getting to later streets; draws benefit from ending the hand early.

Now we use these assumptions to our advantage and figure out the best way to play each hand based on the type of equity it has. As you read further, keep in mind that the suggestions I make are very general and based on looking at the player pool as a whole. Against strong or tricky opponents who are good at hand-reading, you must adapt your lines accordingly when trying to form profitable lines and optimize your c-bet frequencies.

How To Play Made Hands

Since we know that made hands have stable equity as streets progress, we generally want to play straightforward and build pots when our opponent's range is weak. The standard play should be to go for as many streets of value as possible. With mid-strength made hands, bet-folding is our friend against most opponents. By bet-folding, I mean you bet for value and then fold if raised. This works best against most weak opponents and ABC type opponents.

However, when our opponent's range for continuing is narrow, we want to avoid building giant pots unless SPR dictates otherwise. When an opponent's range is strong, we tend to want to pot control more often and try to get to showdown without building huge pots. Taking more passive lines such as checking back the flop is often warranted when it's hard to get value from worse hands. Instead, we benefit from keeping in the weaker parts of an opponents range which we can bluff catch against on later streets.

How To Play Draws

With variable equity as streets progress, we know our equity will take a nosedive if we don't get there on the next street. There is no benefit to stringing our opponents out over multiple streets. Therefore, when we have high equity draws, we generally want to exert maximum pressure against the weak to medium strength hands in our opponent's range. The idea is to elicit folds with a profitable frequency based on fold equity.

The standard play should be to try to leverage your stack on the flop or turn whether against strong or weak ranges. A typical line is to go for flop check-raises or turn check-shoves out of position against aggressive opponents. In position, making slightly larger bets, in general, is also a good tactic when playing a draw. Whatever line you think will exert maximum pressure against the weaker made hands in your opponent's range is key. Just represent whatever your opponent will believe to be legitimately strong, whatever that happens to look like in a particular dynamic based on his perceived level of thinking.

The exception is when you hold a lower equity draw. In that case, it is often better to take whatever line will allow you to realize equity with a higher frequency. The balance between collecting on fold equity and equity realization is a constant struggle for good players and something you will need to actively work on.

Equity Denial

Equity denial is a concept I have been talking about for several years that has finally come to the forefront of poker thinking. Basically, it means when your opponent is forced to fold a reasonable amount of equity against your hand or range. In my opinion, the concept is basically the same as protection and mostly applies to when you have a weak made hand and are looking to 'protect' the hand versus the parts of your opponent's range that are too weak to continue to aggression but have a fair amount of equity against you. In other words, equity denial is an argument against pot controlling marginal made hands, especially on a dynamic board where there's more potential for an opposing range to catch up.

However, this does not mean that we should just go hog wild with all of our made hands and just bet bet bet our opponents into oblivion. In fact, a large portion of made hands in our range might benefit from more passive play. For example, let's say we hold a weak top pair or a mid pair type hand and the board is QT7. This is a fairly dynamic board and our opponent will certainly have parts of his range that can give him the best hand on the next street. Even so, he also likely has numerous hands that might give him a second best hand against us as well. This fact alone often cancels out the benefit of equity denial by itself.

Additionally, if we factor in the times that aggressive opponents might bluff on the turn and/or river, pot controlling actually becomes a lot more attractive with some mid-strength and even weaker strength made hands. The better we get at reading hands and opponents, the better we can pick and choose particular runouts to bluff catch or even raise our opponent off better hands on later streets.

Which Hands Should We Protect or Deny Equity?

In my opinion, the only hands we should really ever be protecting just for the sake of denial are weak made hands that will very often be caught up with by the river anyway. Underpairs and bottom pairs are the best candidates. Every other part of our made hand range benefits from more nuanced play with specific adjustments against each opponent we face. Basically, what I am saying here is that we should be careful in using 'equity denial' as a reasoning for betting except in very specific instances. Most of the time there are other factors that we should be considering, namely our equity type versus our specific opponent's range, in making betting line decisions.

Equity in Multi-Way Pots

When we look at how variable and stable equity works, we can make a couple of assumptions about how being multi-way might affect the value of a made hand versus a draw. First off, we know that against stronger ranges it's better to have a draw. Secondly, we know that made hands like top pair go down in value the more ranges that are involved in the hand. It only makes sense that the more ranges you add to the mix, the stronger your hand will need to be in order to profitably stack off.

Therefore, when holding a mid-strength made hand, we should be more inclined to play a pot control type line when involved in a multi-way pot. Conversely, we should theoretically play draws (to the nuts) much more aggressively the more ranges we are up against. This is partially due to the increased amount of dead money in the pot but also because something magical happens when we end up in a multi-way situation against two strong ranges on the flop. Take a look at the following Pokerstove examples:

Draw Versus Two Made Hand Range

In the first example, we have an Ace-High flush draw versus a range of made hands on a K72 board. We have a respectable equity of 40%. In spots where we have only a small amount of fold equity, we can profitably stack off most of the time. In the second example, look what happens when our flush draw is up against two made hand ranges. We are actually quite a bit ahead of both of them! In this spot, we would gladly get the money in multi-way every single time. Even though we would only be winning 36% of the time, we would be raking in the long-term EV dollars. And, if you factor in that sometimes our opponent(s) might get the money in with an inferior flush draw, this situation becomes a fist pump. Which leads us to a conclusion.

Nut draws play extremely well in multi-way pots and often do not require fold equity to profitably commit to the pot.

Interestingly, even if you only included the absolute top of our opponents' ranges, we still would have a reasonably high amount of equity for a multi-way spot, as shown below.

This example proves the concept of stable equity over ranges, exhibited by draws.

Balancing Our Play

One of the main concerns of many stronger players is in balancing out their ranges. It's true that you have to be careful not to play one type of holding the same way every time and never take similar lines across the spectrum of your entire range. Therein lies the beauty of focusing on equity when making your post-flop decisions.

When you base your decisions on the perceived range of an opponent, you are already baking into the equation what he or she is thinking about your range. The use of stable and variable equity allows us to counter what our opponents are doing before they even have the chance to adjust to us. Only the very strongest opponents you will face will be balanced enough for us to be overly concerned about how balanced our own play is. The vast majority of your mental resources should be dedicated to an exploitative style of poker, not trying to play game theory optimal.

My advice is to build a core strategy that is inherently balanced and then make targeted adjustments based on the opponents you face. Those adjustments include equity considerations, tweaked based on stable and variable equities. It's not as complicated as it sounds, once you understand how it works in a practical way. Hopefully, this article has shed some light on the subject for you.

Summary

Overall, understanding equity in poker all comes down to the relationship between how made hands or draws play out versus opponent ranges. Among the concepts you must master to win at poker is to develop our sense of how to approach post-flop play using equity and ranges as a tool to optimize your lines based on the information at hand. By adjusting your lines according to the makeup of those ranges, you can maximize your profit while also simplifying the decision-making process.

In our poker math and probability lesson it was stated that when it comes to poker; 'the math is essential'. Although you don't need to be a math genius to play poker, a solid understanding of probability will serve you well and knowing the odds is what it's all about in poker. It has also been said that in poker, there are good bets and bad bets. The game just determines who can tell the difference. That statement relates to the importance of knowing and understanding the math of the game.

In this lesson, we're going to focus on drawing odds in poker and how to calculate your chances of hitting a winning hand. We'll start with some basic math before showing you how to correctly calculate your odds. Don't worry about any complex math – we will show you how to crunch the numbers, but we'll also provide some simple and easy shortcuts that you can commit to memory.

Basic Math – Odds and Percentages

Odds can be expressed both 'for' and 'against'. Let's use a poker example to illustrate. The odds against hitting a flush when you hold four suited cards with one card to come is expressed as approximately 4-to-1. This is a ratio, not a fraction. It doesn't mean 'a quarter'. To figure the odds for this event simply add 4 and 1 together, which makes 5. So in this example you would expect to hit your flush 1 out of every 5 times. In percentage terms this would be expressed as 20% (100 / 5).

Here are some examples:

- 2-to-1 against = 1 out of every 3 times = 33.3%

- 3-to-1 against = 1 out of every 4 times = 25%

- 4-to-1 against = 1 out of every 5 times= 20%

- 5-to-1 against = 1 out of every 6 times = 16.6%

Converting odds into a percentage:

- 3-to-1 odds: 3 + 1 = 4. Then 100 / 4 = 25%

- 4-to-1 odds: 4 + 1 = 5. Then 100 / 5 = 20%

Converting a percentage into odds:

- 25%: 100 / 25 = 4. Then 4 – 1 = 3, giving 3-to-1 odds.

- 20%: 100 / 20 = 5. Then 5 – 1 = 4, giving 4-to-1 odds.

Another method of converting percentage into odds is to divide the percentage chance when you don't hit by the percentage when you do hit. For example, with a 20% chance of hitting (such as in a flush draw) we would do the following; 80% / 20% = 4, thus 4-to-1. Here are some other examples:

- 25% chance = 75 / 25 = 3 (thus, 3-to-1 odds).

- 30% chance = 70 / 30 = 2.33 (thus, 2.33-to-1 odds).

Some people are more comfortable working with percentages rather than odds, and vice versa. What's most important is that you fully understand how odds work, because now we're going to apply this knowledge of odds to the game of poker.

The right kind of practice between sessions can make a HUGE difference at the tables. That's why this workbook has a 5-star rating on Amazon and keeps getting reviews like this one: 'I don't consider myself great at math in general, but this work is helping things sink in and I already see things more clearly while playing.'

Instant Download · Answer Key Included · Lifetime Updates

Counting Your Outs

Before you can begin to calculate your poker odds you need to know your 'outs'. An out is a card which will make your hand. For example, if you are on a flush draw with four hearts in your hand, then there will be nine hearts (outs) remaining in the deck to give you a flush. Remember there are thirteen cards in a suit, so this is easily worked out; 13 – 4 = 9.

Another example would be if you hold a hand like and hit two pair on the flop of . You might already have the best hand, but there's room for improvement and you have four ways of making a full house. Any of the following cards will help improve your hand to a full house; .

The following table provides a short list of some common outs for post-flop play. I recommend you commit these outs to memory:

Table #1 – Outs to Improve Your Hand

The next table provides a list of even more types of draws and give examples, including the specific outs needed to make your hand. Take a moment to study these examples:

Table #2 – Examples of Drawing Hands (click to enlarge)

Counting outs is a fairly straightforward process. You simply count the number of unknown cards that will improve your hand, right? Wait… there are one or two things you need to consider:

Don't Count Outs Twice

There are 15 outs when you have both a straight and flush draw. You might be wondering why it's 15 outs and not 17 outs, since there are 8 outs to make a straight and 9 outs for a flush (and 8 + 9 = 17). The reason is simple… in our example from table #2 the and the will make a flush and also complete a straight. These outs cannot be counted twice, so our total outs for this type of draw is 15 and not 17.

Anti-Outs and Blockers

There are outs that will improve your hand but won't help you win. For example, suppose you hold on a flop of . You're drawing to a straight and any two or any seven will help you make it. However, the flop also contains two hearts, so if you hit the or the you will have a straight, but could be losing to a flush. So from 8 possible outs you really only have 6 good outs.

It's generally better to err on the side of caution when assessing your possible outs. Don't fall into the trap of assuming that all your outs will help you. Some won't, and they should be discounted from the equation. There are good outs, no-so good outs, and anti-outs. Keep this in mind.

Calculating Your Poker Odds

Once you know how many outs you've got (remember to only include 'good outs'), it's time to calculate your odds. There are many ways to figure the actual odds of hitting these outs, and we'll explain three methods. This first one does not require math, just use the handy chart below:

Table #3 – Poker Odds Chart

As you can see in the above table, if you're holding a flush draw after the flop (9 outs) you have a 19.1% chance of hitting it on the turn or expressed in odds, you're 4.22-to-1 against. The odds are slightly better from the turn to the river, and much better when you have both cards still to come. Indeed, with both the turn and river you have a 35% chance of making your flush, or 1.86-to-1.

We have created a printable version of the poker drawing odds chart which will load as a PDF document (in a new window). You'll need to have Adobe Acrobat on your computer to be able to view the PDF, but this is installed on most computers by default. We recommend you print the chart and use it as a source of reference. It should come in very handy.

Doing the Math – Crunching Numbers

There are a couple of ways to do the math. One is complete and totally accurate and the other, a short cut which is close enough.

Let's again use a flush draw as an example. The odds against hitting your flush from the flop to the river is 1.86-to-1. How do we get to this number? Let's take a look…

With 9 hearts remaining there would be 36 combinations of getting 2 hearts and making your flush with 5 hearts. This is calculated as follows:

(9 x 8 / 2 x 1) = (72 / 2) ≈ 36.

This is the probability of 2 running hearts when you only need 1 but this has to be figured. Of the 47 unknown remaining cards, 38 of them can combine with any of the 9 remaining hearts:

9 x 38 ≈ 342.

Now we know there are 342 combinations of any non heart/heart combination. So we then add the two combinations that can make you your flush:

36 + 342 ≈ 380.

The total number of turn and river combos is 1081 which is calculated as follows:

(47 x 46 / 2 x 1) = (2162 / 2) ≈ 1081.

Now you take the 380 possible ways to make it and divide by the 1081 total possible outcomes:

380 / 1081 = 35.18518%

This number can be rounded to .352 or just .35 in decimal terms. You divide .35 into its reciprocal of .65:

0.65 / 0.35 = 1.8571428

And voila, this is how we reach 1.86. If that made you dizzy, here is the short hand method because you do not need to know it to 7 decimal points.

The Rule of Four and Two

A much easier way of calculating poker odds is the 4 and 2 method, which states you multiply your outs by 4 when you have both the turn and river to come – and with one card to go (i.e. turn to river) you would multiply your outs by 2 instead of 4.

Imagine a player goes all-in and by calling you're guaranteed to see both the turn and river cards. If you have nine outs then it's just a case of 9 x 4 = 36. It doesn't match the exact odds given in the chart, but it's accurate enough.

What about with just one card to come? Well, it's even easier. Using our flush example, nine outs would equal 18% (9 x 2). For a straight draw, simply count the outs and multiply by two, so that's 16% (8 x 2) – which is almost 17%. Again, it's close enough and easy to do – you really don't have to be a math genius.

Do you know how to maximize value when your draw DOES hit? Like…when to slowplay, when to continue betting, and if you do bet or raise – what the perfect size is? These are all things you'll learn in CORE, and you can dive into this monster course today for just $5 down…

Conclusion

In this lesson we've covered a lot of ground. We haven't mentioned the topic of pot odds yet – which is when we calculate whether or not it's correct to call a bet based on the odds. This lesson was step one of the process, and in our pot odds lesson we'll give some examples of how the knowledge of poker odds is applied to making crucial decisions at the poker table.

As for calculating your odds…. have faith in the tables, they are accurate and the math is correct. Memorize some of the common draws, such as knowing that a flush draw is 4-to-1 against or 20%. The reason this is easier is that it requires less work when calculating the pot odds, which we'll get to in the next lesson.

Related Lessons

By Tom 'TIME' Leonard

Poker Range Equity

Tom has been writing about poker since 1994 and has played across the USA for over 40 years, playing every game in almost every card room in Atlantic City, California and Las Vegas.